Category: Latest News

-

-

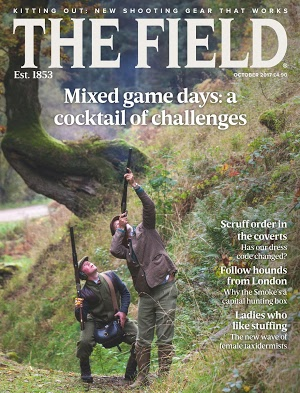

Article in ‘The Field Magazine’

Shooting stars for stocking trade – The Field Magazine – Oct 2017 The once humble shooting sock is enjoying something of a renaissance, thanks to a certain breed of sporting gentlemanThere are few areas in a chap’s life in which he’s permitted to be properly flamboyant. Cufflinks and waistcoats top the list but these do not materially…

-

-

Winners of the “Best Organic Textile Product”

We are delighted to announce that we are the winners of the “Best Organic Textile Product” at the ‘2010 Natural and Organic Products Europe Show’ in conjunction with the Soil Association Organic Awards at Olympia on Sunday 11th April.We presented four small Colletions to be judged: The Caillagh Weave Collection, The Victorian Lace Collection, The…

-

-

Prince of Wales shows the way to lead wool back into the fashion fold.

Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the sweater along comes a man with a plan, in doublebreasted wool.The Prince of Wales is attempting to rebrand a material favoured by the nation’s grandmothers — and Val Doonican — as a fashionable and eco-friendly fabric that consumers will choose for clothes and…

-

Nature’s Finest article on WKD.

We were recently lucky enough to have this lovely article written about us.